Attack

http://www.bbc.co.uk/learningzone/clips/siegfried-sassoon-the-attack-poem-only/1252.html

At dawn the ridge emerges massed and dun

In the wild purple of the glow’ring sun,

Smouldering through spouts of drifting smoke that shroud

The menacing scarred slope; and, one by one,

Tanks creep and topple forward to the wire.

The barrage roars and lifts. Then, clumsily bowed

With bombs and guns and shovels and battle-gear,

Men jostle and climb to meet the bristling fire.

Lines of grey, muttering faces, masked with fear,

They leave their trenches, going over the top,

While time ticks blank and busy on their wrists,

And hope, with furtive eyes and grappling fists,

Flounders in mud. O Jesus, make it stop!

Dame Helen Mirren recites the poem:

http://www.videosurf.com/video/dame-helen-mirren-attack-by-siegfried-sassoon-75623698

Sassoon and poets of the Great War

http://www.videosurf.com/video/siegfried-sassoon-and-poets-of-the-great-war-103851170

Suicide in the Trenches

I knew a simple soldier boy

Who grinned at life in empty joy,

Slept soundly through the lonesome dark,

And whistled with the early lark.

In winter trenches, cowed and glum,

With crumps and lice and lack of rum,

He put a bullet through his brain.

No one spoke of him again.

…

You smug-faced crowds with kindling eye

Who cheer when soldier lads march by,

Sneak home and pray you’ll never know

The hell where youth and laughter go.

Repression of War Experience

Now light the candles; one; two; there’s a moth;

What silly beggars they are to blunder in

And scorch their wings with glory, liquid flame –

No, no, not that, – it’s bad to think of war,

When thoughts you’ve gagged all day come back to scare you;

And it’s been proved that soldiers don’t go mad

Unless they lose control of ugly thoughts

That drive them out to jabber among the trees.

Now light your pipe; look, what a steady hand.

Draw a deep breath; stop thinking; count fifteen,

And you’re as right as rain…

Why won’t it rain?…

I wish there’d be a thunder-storm tonight,

With bucketsful of water to sluice the dark,

And make the roses hang their dripping heads.

Books; what a jolly company they are,

Standing so quiet and patient on their shelves,

Dressed in dim brown, and black, and white, and green,

And every kind of colour. Which will you read?

Come on; O do read something; they’re so wise.

I tell you all the wisdom of the world

Is waiting for you on those shelves; and yet

You sit and gnaw your nails, and let your pipe out,

And listen to the silence: on the ceiling

There’s one big, dizzy moth that bumps and flutters;

And in the breathless air outside the house

The garden waits for something that delays.

There must be crowds of ghosts among the trees, –

Not people killed in battle – they’re in France –

But horrible shapes in shrouds – old men who died

Slow, natural deaths – old men with ugly souls,

Who wore their bodies out with nasty sins.

. . .

You’re quiet and peaceful, summering safe at home;

You’d never think there was a bloody war on! …

O yes, you would … why, you can hear the guns.

Hark! Thud, thud, thud, – quite soft … they never cease –

Those whispering guns – O Christ, I want to go out

And screech at them to stop – I’m going crazy;

I’m going stark, staring mad because of the guns.

Repression of War Experience by Siegfried Sassoon

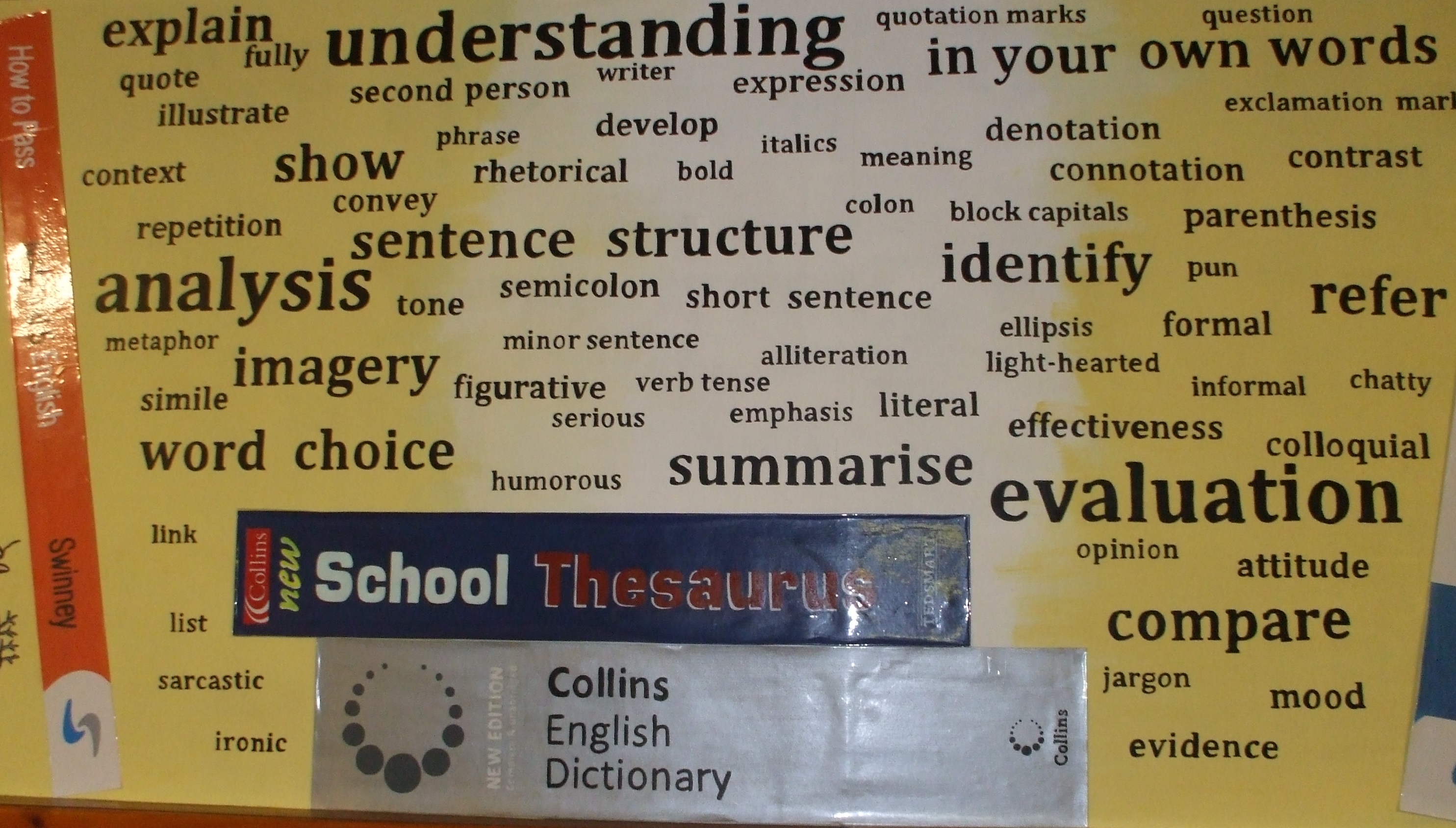

Although the title, ‘Repression of a War Experience’ indicates the content of the poem, the mundane opening line may not meet the reader’s expectations with its apparent calm and fixation with candles and moth. The poem, which is written in blank verse, opens with an apparent command: “Now light the candles”. Use of the word ‘now’ initially suggests that the speaker is guiding someone to complete a series of tasks, which have already been commenced. To enhance this idea the first line continues, “one; two;” The structure of this line is broken up with the use of semi-colons, which create a more definite pause than a comma and that are also suggestive of a list, emphasising the assumption that the speaker is giving a series of instructions.

The second and third lines seem to carry on the idea of the speaker’s distraction with the moth, which is introduced at the end of the first line: “there’s a moth”. However, a more in-depth analysis would suggest that the moth might be compared to the soldiers who, “blunder in […] with glory” only to “scorch their wings.” This would suggest that the moth’s actions take on a symbolic role in the speaker’s mind. Indeed, the suggestion of an internal thought process, which leans towards war-time experiences is carried forth to the following three lines:

No, no, not that, – it’s bad to think of war,

When thoughts you’ve gagged all day come back to scare

You;

It is at this point that the reader realises the speaker is playing a conscious role in instructing their own actions in an attempt to forget or suppress painful or frightening memories of war: memories that have been successfully ‘gagged’ all day. This might be linked to the speaker’s apparent attempt to ‘fill’ his time as the day is ending and evening or night has drawn in upon him. It is during these hours that the speaker must try his hardest to avoid such thoughts.

The use of a conscious internal monologue thought out in second person narrative is interrupted by the speaker’s unconscious internal monologue. This unconscious monologue punctuates the conscious thought process at random times: “there’s a moth” and, “No, no, not that…”. The conscious internal monologue uses a second person mode of narration in order to direct the speaker in his actions through a controlled and calm period filled with the lighting of candles; observance of moths; the lighting of a pipe and other minor distractions. It might seem obvious to the reader that the speaker is scared of these repressed thoughts, but it is also more than fear that creates this repression:

And it’s been proved that soldiers don’t go mad

Unless they lose control of ugly thoughts

That drive them out to jabber among the trees.

This highlights to the reader that the speaker has taken on the advice of others (see the Lancet document) in their attempt to repress their worst thoughts. With the use of the word, ‘proved’, one might assume medical experts or psychoanalysts, have advised that soldiers (or ex-soldiers) must not think about any war-time experiences that they find to be emotionally unsettling. This might further explain the speaker’s use of second person narration. Not only does this suggest that the speaker is disengaged from their emotions by simply focussing on narrating their own actions, but also that their words are not their own.

This idea is carried forward to the next stanza, whereby the speaker indicates that they must, “count fifteen” as though this is the advice they have been given to maintain their calm and steer away from their darker thoughts. The simile, “And you’re as right as rain” is not convincing and is also suggestive of the words of another or others who have imposed this notion on the speaker who must calmly comply with their advisors’ pressures to be ‘normal’.

The following line confirms that the speaker is not in a normal state: “Why won’t it rain?…”. This is a direct observation of what is outside, but also has further hidden meanings as well. In its simplest form this line is suggestive of a desire to see rain, which will, “sluice the dark”. However, there is more depth to this. The speaker is “not as right as rain”, hence, their desire to be made all right and to be metaphorically salved or cleansed, through the sluicing of their darkest thoughts. It is also suggestive of a delay. This theme of delay is carried forward to the rest of the poem. Indeed, even from the opening lines there is a sense of anticipation that something will happen -perhaps emphasised by the use of ellipsis after this question.

This is further emphasised in the following stanza, which conveys the opening idea of books that will not or cannot be read. There is also a build up of tension through the anxiety felt by the speaker here as they see war in commonplace objects or action. Even the books take on the suggestion of soldiers who stand, “quiet and patient” as though they are waiting for an order to march on or go over the top. And although the speaker notes the books are dressed in, “every kind of colour” it is only the colour of fatigues that the speaker notes in this “company” of books: “Dressed in dim brown, and black, and white, and green.”

The notion of anxiety is further built up as the speaker sits and chews his nails: “You sit and gnaw your nails”. This image is one of someone who is anxious. It is also suggestive of his nervous tension as he awaits that something, which seems increasingly inevitable. Although the speaker listens to the silence he also notes the movement of the moth, which “bumps and flutters” on the ceiling. Even though the moth is growing dizzy with this action, it continues to flutter about. Again, this extends and carries forward the symbolism presented in the first stanza. The moth might be said to be like the soldiers who are forced towards the dangerous flame or burning lights of warfare.

The speaker notes that the “garden waits for something that delays”, and this makes the idea that something must happen more explicit. The speaker seems to see “crowds of ghosts among the trees”. However, although he has a tendency to think on death, he notes in the next verse that these ghosts would not be, “people killed in battle” as, “they’re in France”. Instead, he assumes that they must be the ghosts of, “old men who died/ Slow, natural deaths”. There is a suggestion that the speaker finds such deaths distasteful as he says they must have had, “ugly souls”. There is a contrast to be made between these men who had the ability to wear their bodies out, commit sins and die of natural causes, and the men or youths who have died in France before their time. The old men are not vivid, but simply, “shapes in shrouds” unlike the young men whose images he must suppress.

The final verse is the most powerful, and opens with a statement that appears to be an attempt at self-reassurance: “You’re quiet and peaceful, summering safe at home”. However, the line ends with a semi-colon which extends a link to the next line: “You’d never think there was a bloody war on!” The exclamation mark emphasises the violence of this statement and the impending hysteria of the speaker. The words bloody war, are as much a statement of the violence of this war as they are a cursing of it.

Finally, the speaker can no longer repress their thoughts. Just as the books providing “all the wisdom of the world” are not accessed by the speaker who can find no answers for his problem within their ‘wise’ pages, equally the wisdom of the experts who claim the soldier-speaker is fine is reminiscent of an empty wisdom lacking in answers. The speaker notes the never ending “Thud, thud, thud” of the guns as they confuse the thudding noise of the moth with the sound of gunfire, an obvious example of the terror they feel at the disturbing images that exist within their own mind. Although they are “safe” at home, they are not safe from their own visions. The poem ends in the first person and the honest – previously unspoken but much anticipated statement – that in their ignorance of this condition, we the reader would call shell-shock, the speaker feels they are going, “stark, staring mad”.

Leave a comment